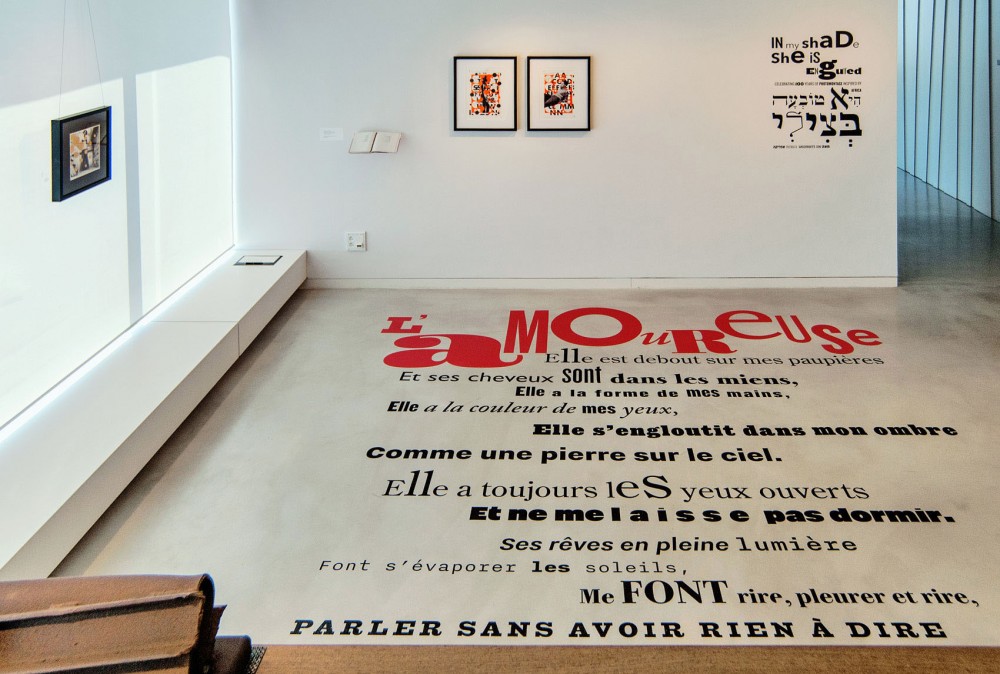

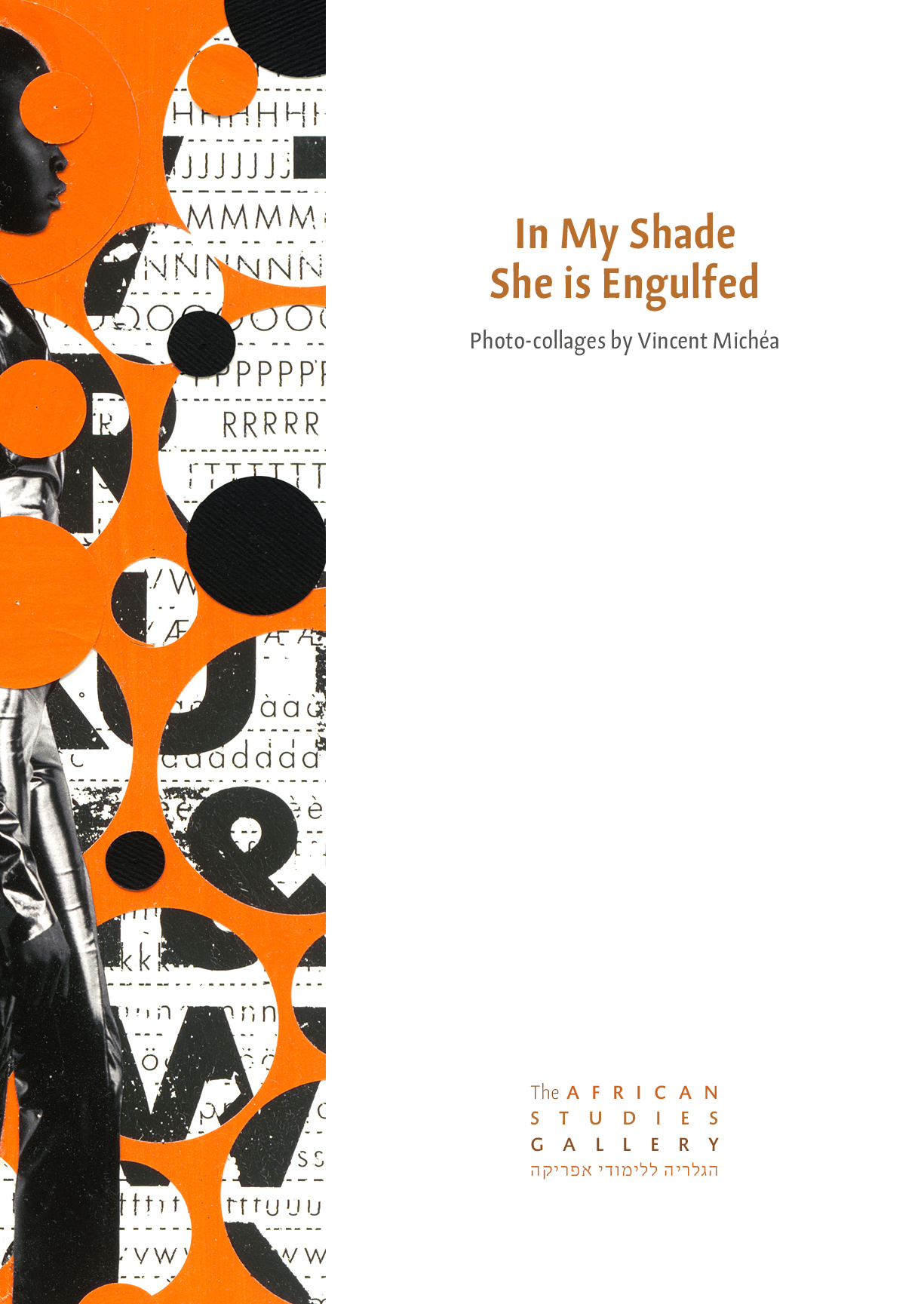

In My Shade She is Engulfed

November 2016 - January 2017

2016 marks the centennial of Dada and with it, the invention of photomontage. During the turmoil of the First World War, a group of exiles from countries on both sides of the conflict found refuge in Zurich, a neutral city in the middle of a war-torn Europe. They established an artistic movement, Dada, which shook the foundations of the art world.

In My Shade She is Engulfed includes a floor work, a silhouette extracted from a drawing made by Marcel Janco as an invitation for the first Dada evening. It is displayed alongside a rare female sculpture from the Basa group in Liberia. The similarity between the two works is startling; as there is no chance that Yanko have seen the work. He must have fantasized, as many other artists of the 20th century did in relation to Africa and the arts of the noble savage. Displayed next to this arrangement, is a photomontage by Guy Avital, a contemporary Israeli artist. The link between the works raises the question of whether modern art could have existed without the influence of Africa. Moreover, what would contemporary art will look like without the possibilities that African gave it, whether real or imagined. Whatever the answers may be, Africa never gets the credit it deserves and remains engulfed in the Western shade.

Two traits are associated with the Dadaists: the use of collage/photomontage, and their obsession with the primitive. The introduction of the collage technique caused a rift in the previously assumed integrity of artistic materials and the conventional unity of artistic illusion. The Primitive served to conjure up a primeval state of consciousness, considered by many modern artists to be a more fundamental mode of thinking and seeing than the conscious mind distracted by modern life.

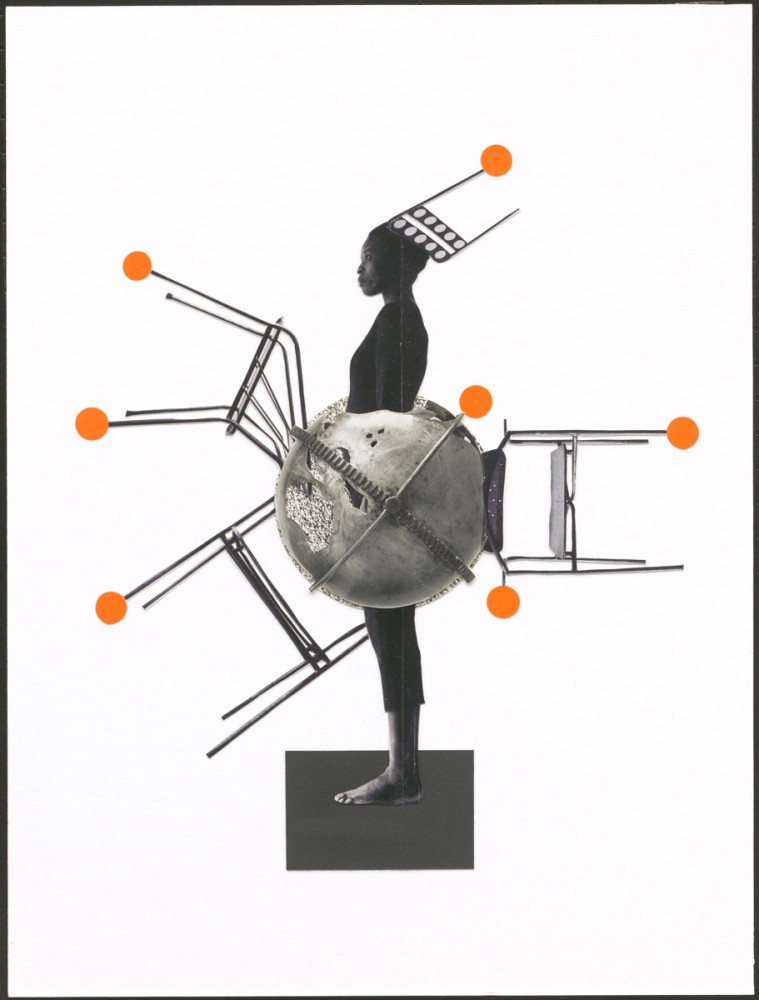

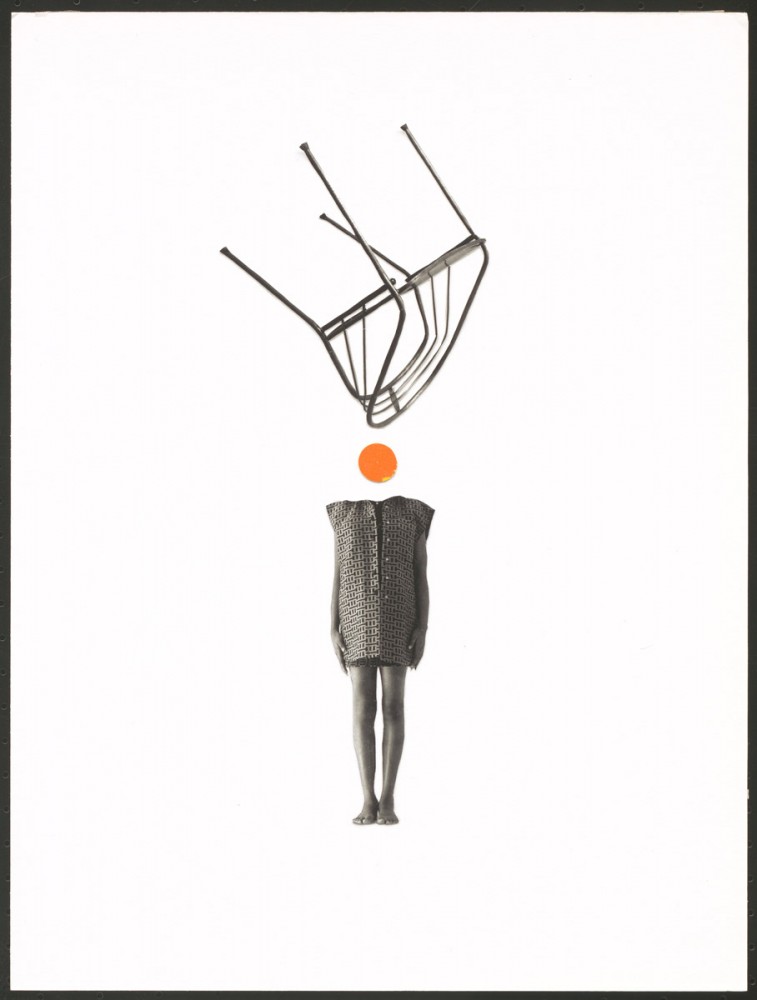

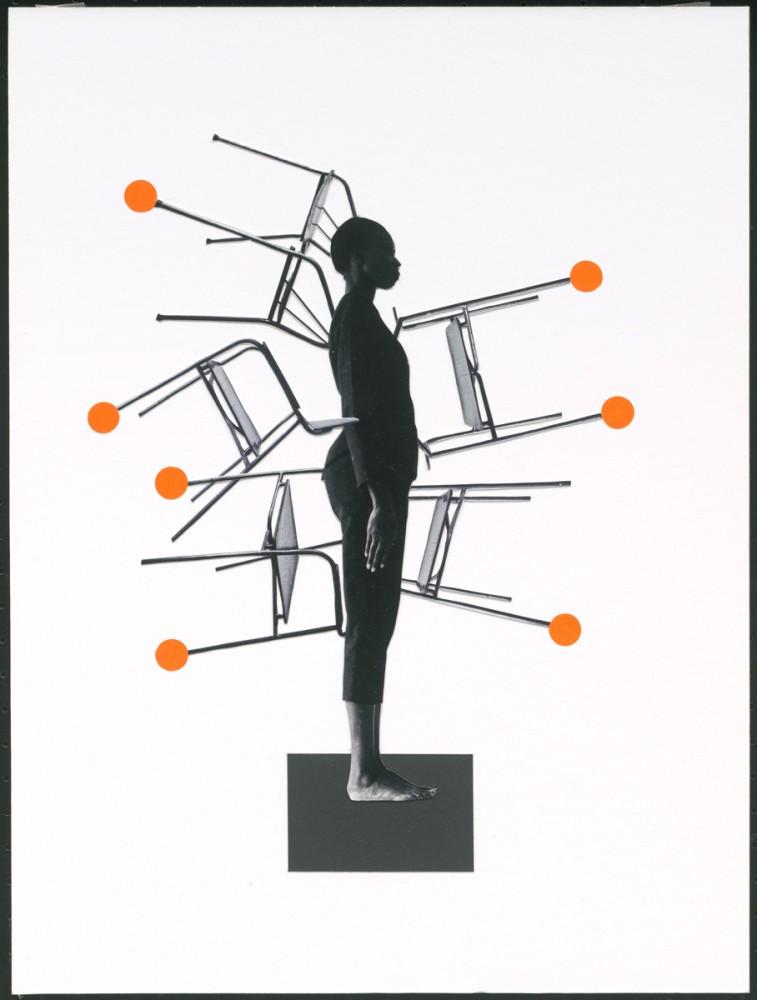

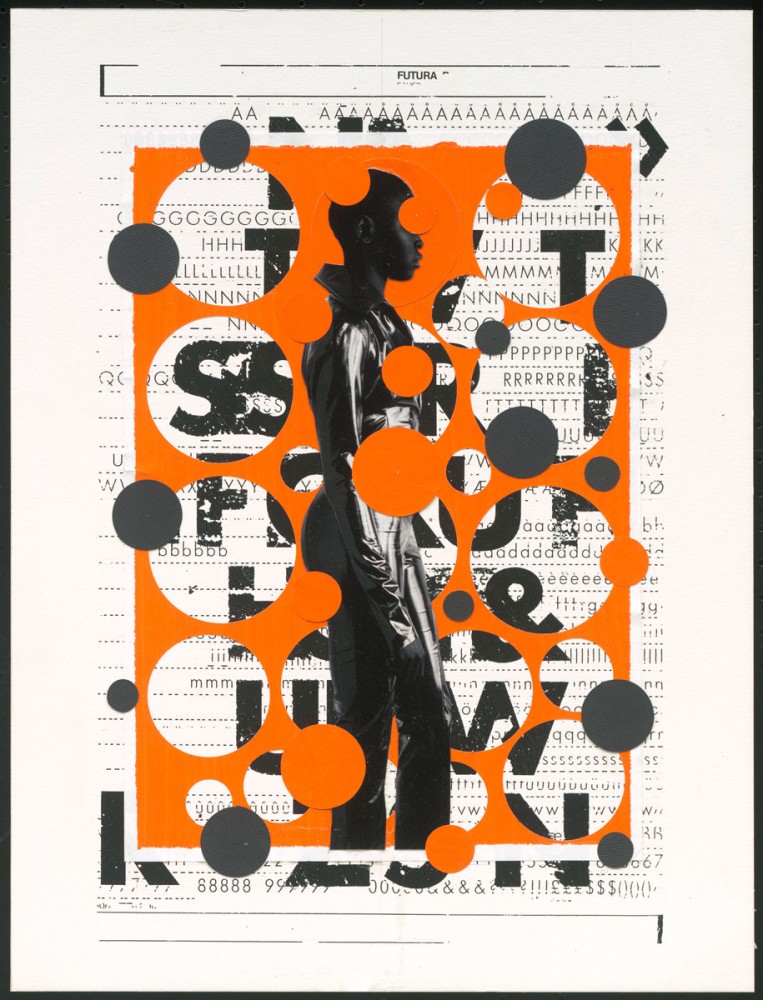

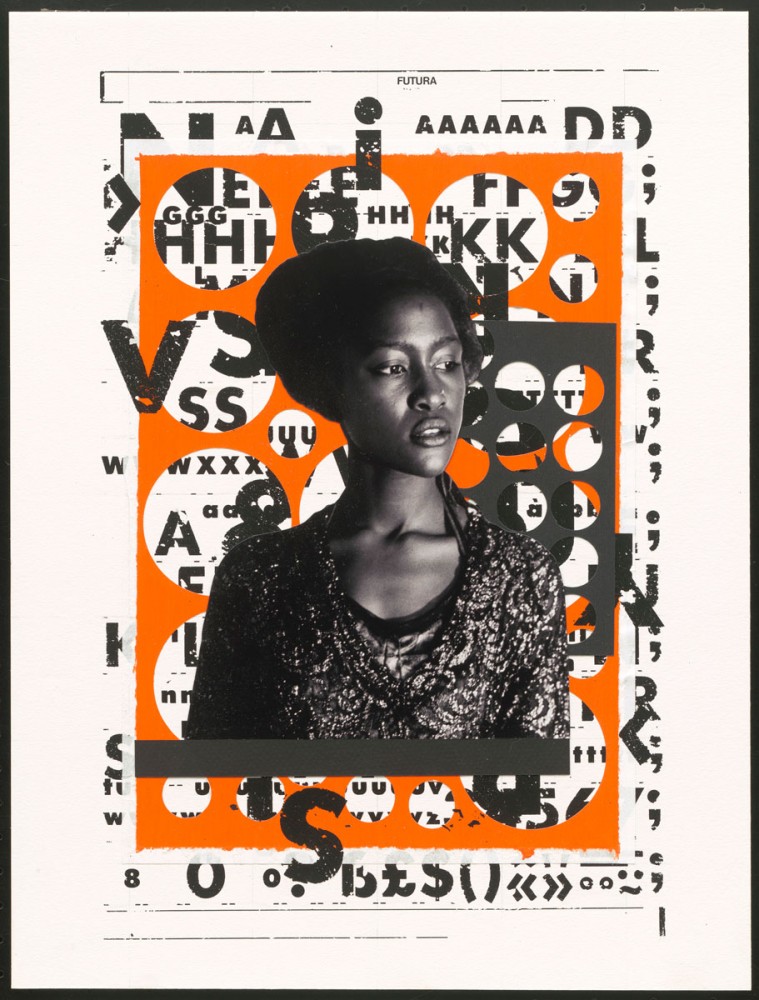

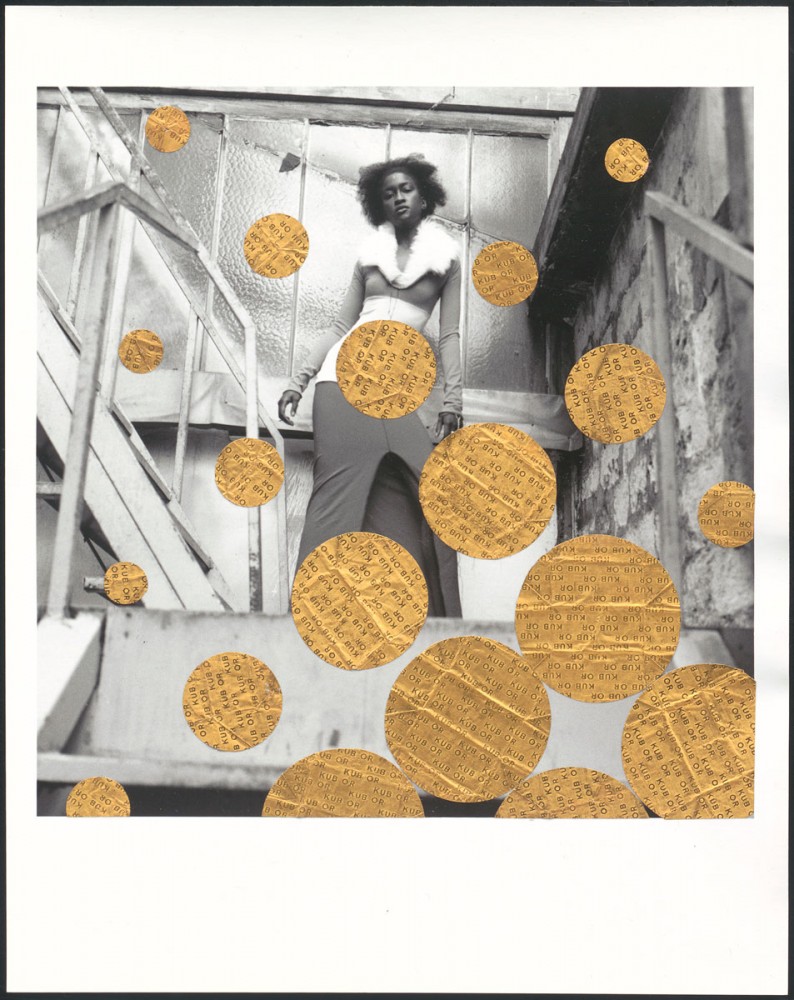

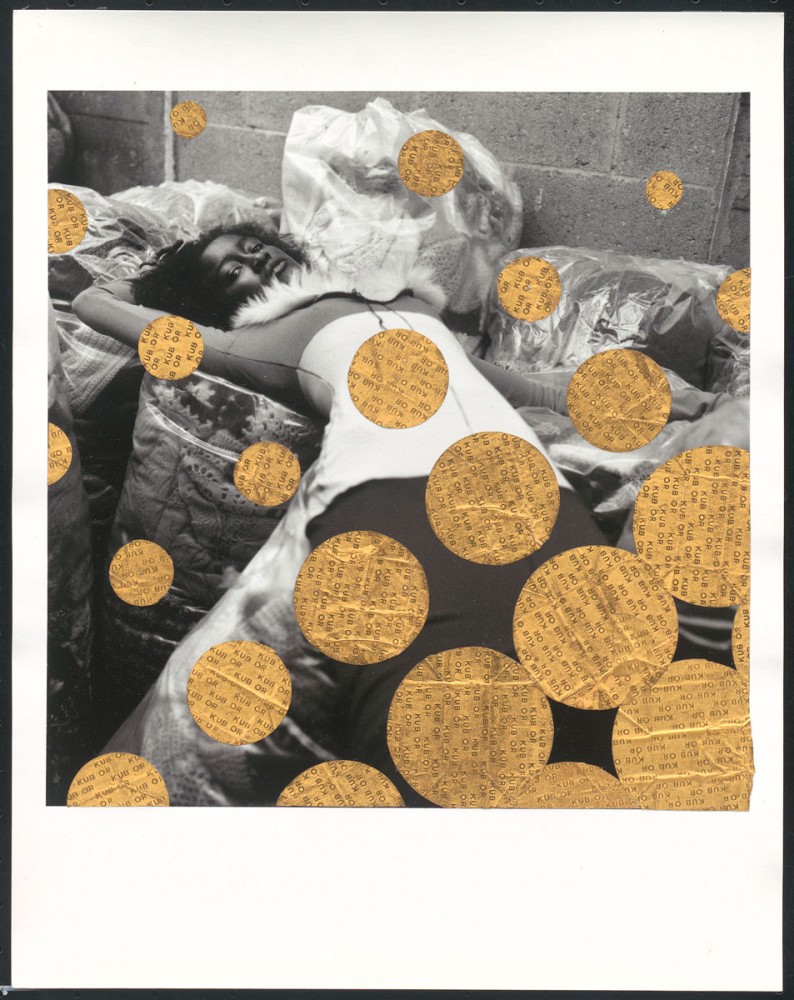

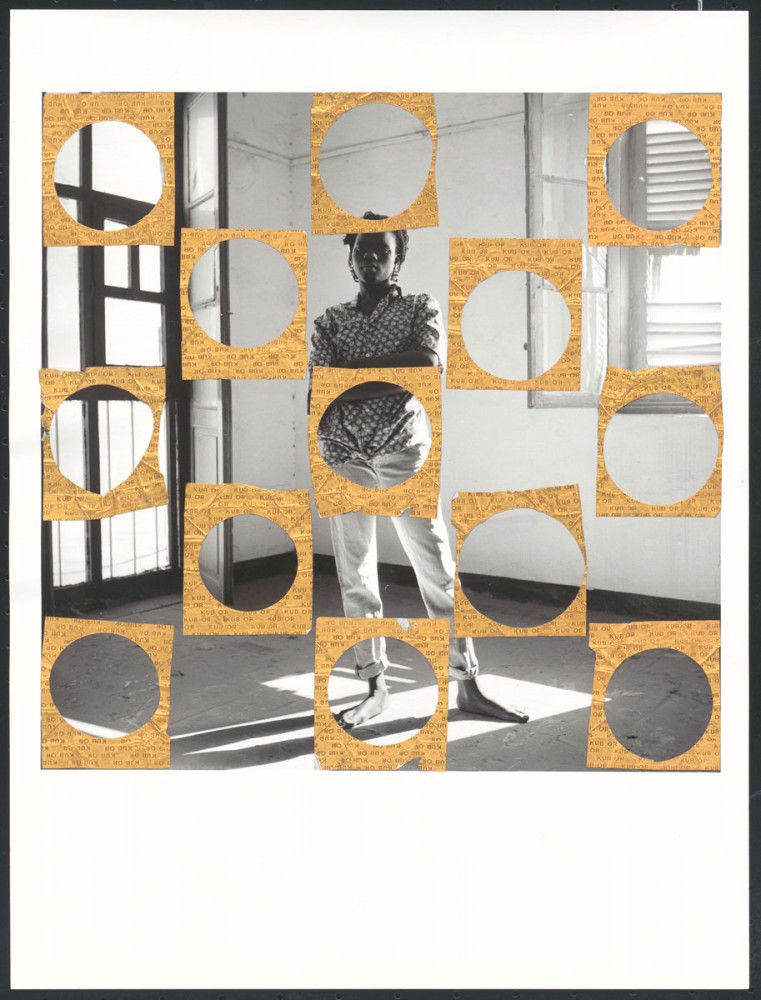

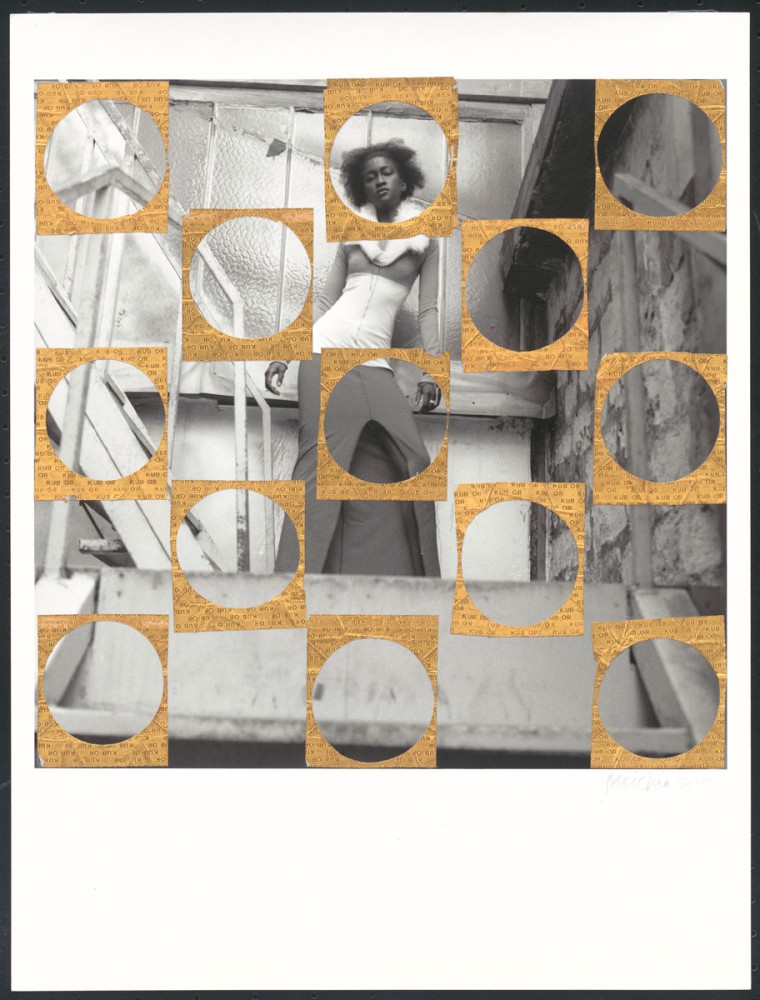

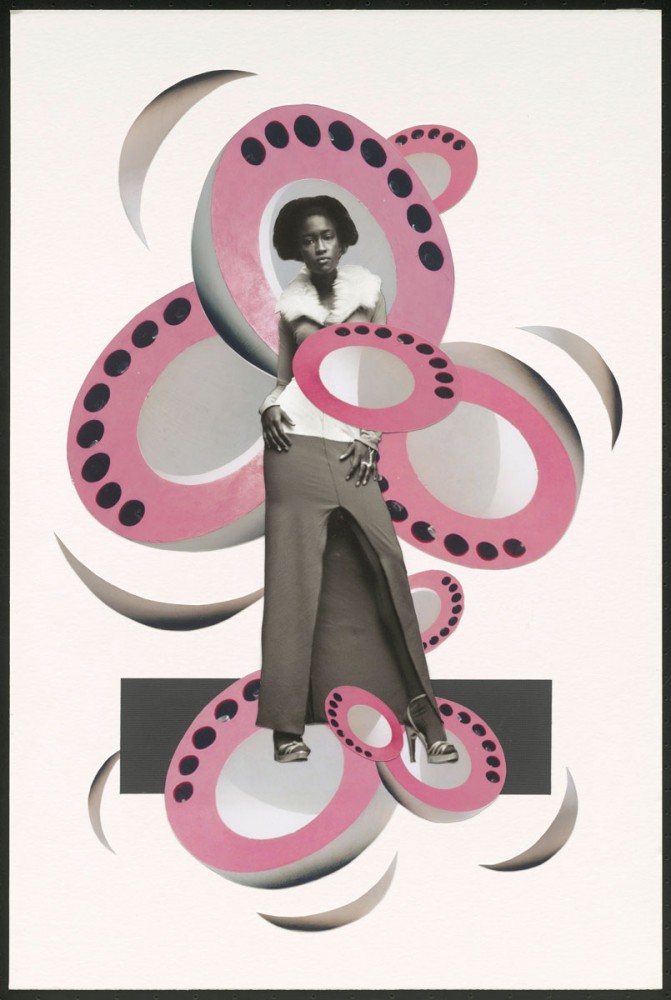

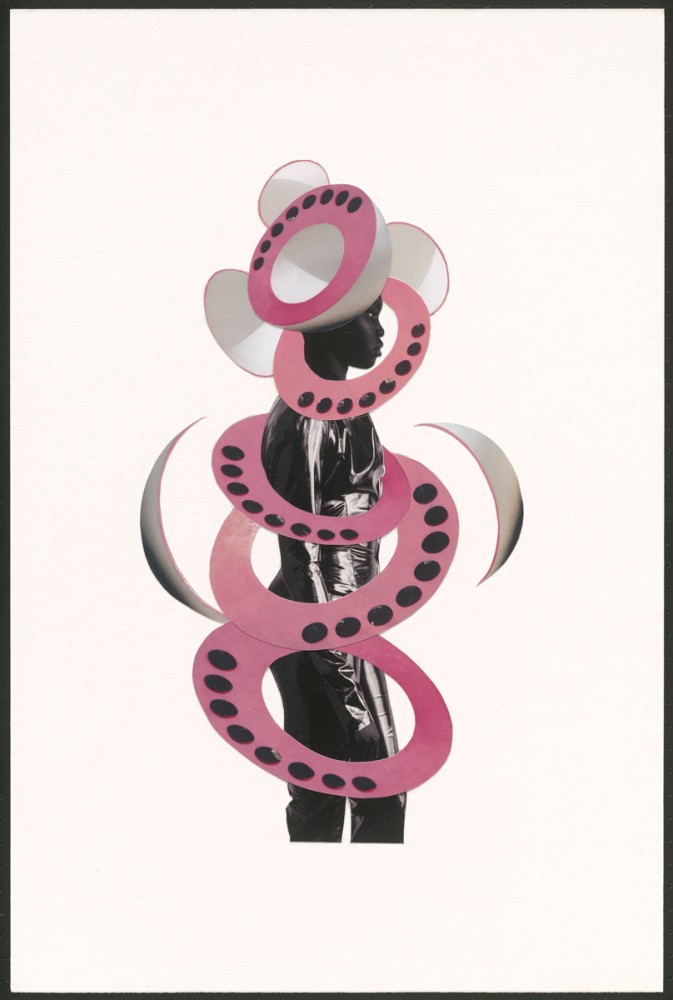

In My Shade She is Engulfed is centered on collage works by Vincent Michéa. Unlike Dada artists who deconstructed images in order to create a new artistic language, Michéa (born 1963, works between Dakar and Paris) does not manipulate his photographs, rather leaves them intact and constructs upon them. Michéa’s photomontages are ensembles of photos of his daily life in the African metropolis, engulfed in the rhythms of West African music delivered by the clear shapes and colors of his paper cuts. For Michéa, Africa is not the exotic Other, but his life experience. His work is not the product of a fantasy about the inhabitants of the “Black Continent” but an ode to its people, mainly Senegalese women.